Math and Mining in the Ore Mountains

Deep in the heart of Central Europe, near the border of Saxony and Bohemia, lie the Ore Mountains. Rich in minerals, the Ore Mountains played a central role in the development of European metallurgy. They are home to some of the first European mining operations, and the inhabitants have been mining tin and silver there since the Pre-Classical Era.

For millennia, the region has attracted people looking to make a living. In the 16th century, as truly large-scale mining operations were underway, Georg Agricola arrived in the mining town of Chemnitz. He had just completed his university education, and took on a job as the town physician. He was somewhat out of place–an educated humanist living in a town of people who worked with their hands.

Agricola became deeply involved in the town, eventually becoming the mayor. And during that time, he attempted to apply his university education to the mining industry, writing on geology and mineralogy. He left us with De Re Metallica, a detailed account of metallurgy in the 16th century. It delves into geometry, and the applications of mathematics to planning and executing mining operations.

How much did this mathematical theory influence the actual mining practices of the time? According to historian Thomas Morel, not much.

I think many people, including myself, have a tendency to think of the Scientific Revolution and the Industrial Revolution as connected. To some extent they were related, but Morel does a fantastic job of disentangling the theoretical from the practical, the scholar from the practitioner.

It’s a difficult job, because the practitioners unfortunately don’t leave us a lot of direct descriptions of their work. To figure out the real-world practices at the time of Agricola, Morel looks to sources like mining laws and sermons in mining towns. These are indirect evidence, but are much closer to the daily lives and practicalities of mining than the writings of a Humanist physician.

In De Re Metallica, Agricola focuses on theoretical ideas about practices like determining where to dig a vertical shaft so that it intersects with a tunnel. These descriptions are complete with diagrams showing similar triangles.

Morel suggests that the actual topography of the Ore Mountains makes this idealized case impractical. He looks to diagrams from actual surveyors, and eventually to a sermon about why Martin Luther was awesome.

This is a phenomenal piece of history. Apparently, a sermon by Cyriacus Spangenberg “included a detailed description of this specific surveying procedure that took up four pages.” If you’ve ever been to a Lutheran church, long sermons and extended religious analogies will be familiar. Apparently they have a long tradition, and thankfully for historians, can provide a glimpse into the actual lives of common people.

Morel argues that the practices revealed by these sources differ significantly from those described in De Re Metallica. “Taking Agricola’s words for granted,” Morel writes, “confuses his literary production with the practices of underground surveyors and hinders our understanding of both.” Surveying and mining practices were indeed advancing at this time, but not because the surveyors were reading Humanists and applying their theory.

So to some extent, the intellectual and practical worlds of 16th century mining were advancing along parallel, but non-intersecting paths. To me, this raises the question of how well this case study can be applied to other fields of science and engineering. But this case study was strong enough that I think it helps shift the burden of proof onto claims that scholarship influenced practice.

Morel suggests that as far as any interaction happened between these two worlds, it was a subtle cross-fertilization. According to him, scholars and practitioners were always most interested in the task right in front of them. For Agricola, that may have been introducing new mathematical ideas to his audience (who were specifically not the miners he was writing about). For the surveyor, that was getting the job done efficiently.

The extent and nature of this cross-fertilization is still something that is being explored in the History of Science. The perspective of the practitioners is more difficult to source, and has been somewhat neglected until recently. The relationship between these two worlds is a somewhat open question, and I think it’s one of the more interesting areas of research. If you know of other attempts to tackle this topic, let me know in the comments.

Source:

Thomas Morel, “De Re Geometrica: Writing, Drawing, and Preaching Mathematics in Early Modern Mines,” Isis, Volume 111, no. 1 (2020) https://doi.org/10.1086/707640

The Incredible Power of Steamships

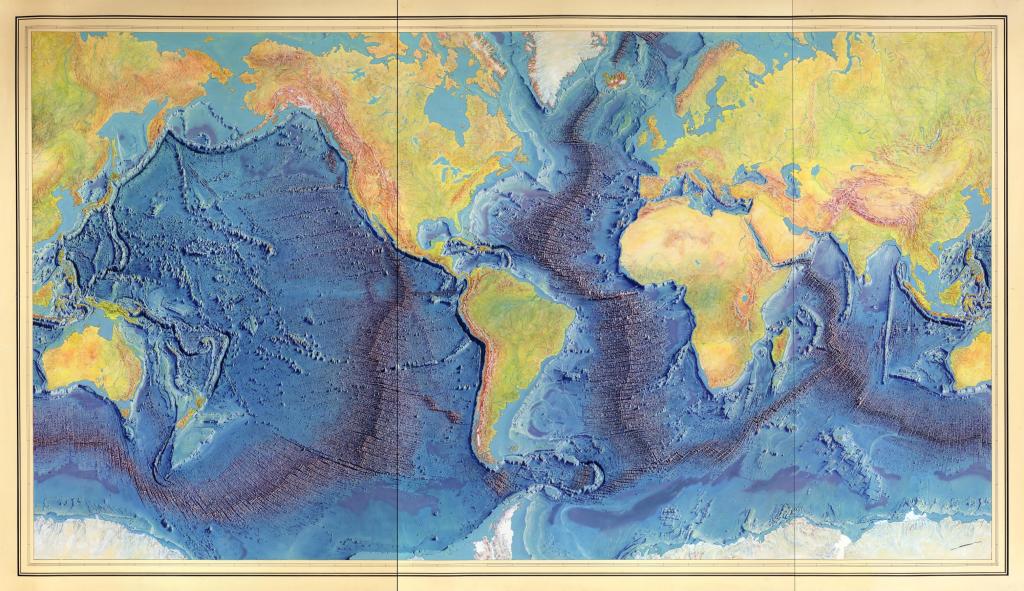

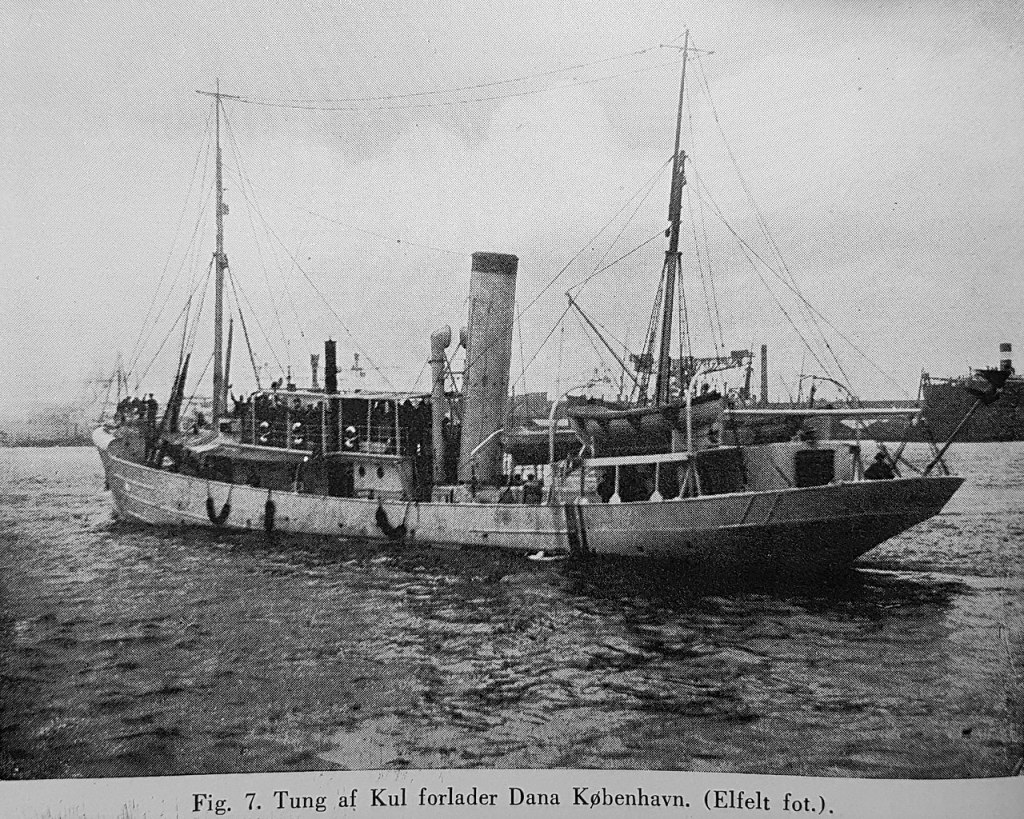

I recently read Neptune’s Laboratory: Fantasy, Fear, and Science at Sea by Antony Adler. In addition to having a fantastic title, it provides a wonderful overview of oceanography as a scientific discipline.

I might do a longer review on this book in the future, but Adler describes the reception of steam ships by 19th century journalists and the public, and I had to share it:

“…it was only upon the arrival of the first commercially viable transatlantic steamship, Sirius, in New York in April of 1838, that newspapers declared the successful ‘annihilation of space and time.’ When soon thereafter some early passenger steamships exploded, at great loss of life, journalists blamed these accidents on ‘a public mind’ that had become ‘completely infatuated with a wish to be borne in the twinkling of an eye’ from place to place.”

I love these glimpses into the perception of new tech throughout time. You see attitudes that seem very persistent across time periods and groups of people.

Source:

Antony Adler, Neptune’s Laboratory: Fantasy, Fear, and Science at Sea

Grey Flag Pirates

Sometimes the history of exploration blends with maritime history. This more general history provides essential context for the history of exploration, so sometimes I might succumb to the temptation to include something not strictly within the confines of the blog’s stated topics. In this case: the pirate officials of the Song Dynasty.

China had problems with piracy along their coast for a good deal of their history. Maritime trade has a tumultuous history in China, partly due to their geography. In The Boundless Sea: A Human History of the Oceans, David Abulafia describes the interesting and controversial way that the Song Dynasty dealt with pirates, by giving them cushy government jobs:

“As more traffic crossed the sea, the temptation to pirates grew exponentially, and convoy escorts were sometimes provided to protect merchant ships; a navy came into being…the corsair Zhu Cong, defeated in 1135, merged his fleet of fifty ships and 10,000 sailors into the Song navy; he was rewarded with the rank of admiral, and others followed the same course. A brief poem circulated:’if you wish to become an official, kill and burn and accept a pardon.’”

Of course, this sparked debate over whether such a policy actually encouraged more piracy. It reminds me a little about the distinction between white hat, black hat, and grey hat hackers.

Source:

David Abulafia, The Boundless Sea: A Human History of the Oceans

Ice Melt Archaeology

A complicating factor in the history of technology is the fact that people don’t always write about the technology they use. This means that a lot of tech is lost to us, unless we actually find physical examples.

An odd side-effect of climate change is that melting ice is revealing archeological treasure troves. One instance, reported in the Smithsonian Magazine, is the Lendbreen route in Norway. Melting ice in the mountain passes has uncovered sleds, skis, clothing and other artifacts from multiple eras.

You can follow the progress of the archeologists at the website Secrets of the Ice, and get updates on Twitter here.